The Seattle Times, November 9, 2009

The Tri-City Herald, November 10, 2009

The Nation (a Pakistani daily), November 10, 2009

Berlin Airlift Changed Enemies Into Solid Allies

©2009 Valerie Kreutzer

During a recent visit to Berlin my apartment overlooked Checkpoint Charlie, the border crossing where Allied and Russian troops grimly faced each other for nearly three decades.

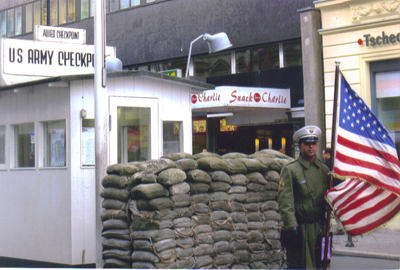

Today, thousands of tourists flock to the white sandbagged hut with its historic “You are leaving the American sector” warning. For a euro you can have your picture taken next to an actor in U.S. army uniform waving the Stars and Stripes. Photo ops often end with hugs and tears, as visitors recall the fear and humiliations that accompanied border crossings when a ten-foot wall surrounded West Berlin.

A museum next to the checkpoint documents the history of a divided Berlin and the bravery of people who tried to escape the repressive communist regime. There’s a photo of Peter Fechter who was shot fleeing and bled to death between the Wall and barbed wire. There’s the reconstructed car with room under the hood for a fiancée. “Don’t even sigh when we get to the border,” she had been warned. There is the inflatable boat that took a pair across the rugged Baltic Sea to Denmark, and remnants of a balloon that brought a whole family to the West.

Twenty years ago, on November 9, 1989, the barriers were finally lifted and millions streamed across the border and dismantled the Wall with pickaxes and bare hands. The euphoria sparked revolutions in neighboring countries and toppled dictatorships from Berlin to the Black Sea. Within months, chants of “We are one people” led to Germany’s reunification.

During my recent travels from north to south and east to west, I listened to Germans reflecting on the past and the 20-year process of becoming one people again.

The fall of the Wall was “a catastrophe,” volunteered the woman next to me on the train to Berlin. She had lived in Erfurt, East Germany, at the time. “I lost my job, I had no money, we lost our way of life. It was a catastrophe all around.” She’s since settled in Berlin and does eldercare. “Actually, it’s the best job I’ve ever had,” she allowed.

“When I get together with East German colleagues,” reported my friend Susan, a psychologist, “they’ll readily admit that they enjoy their new freedom and a better standard of living, but I detect an undercurrent of resentment.”

Communist egalitarianism had provided full employment. But the economy was bankrupt, as it turned out, and the state’s abusive security apparatus kept an iron grip on every citizen. Western democracy offered new freedom, prosperity, and choices. But for some it has been difficult to find their way in the new capitalist world. They are unemployed or underemployed, nostalgic for the past and kvetching in the present.

I got a taste of that when I asked my waiter at a restaurant in the former East Berlin whether he could recommend a good movie—the kind of question every Seattle waiter is eager to answer. “I don’t have time for movies,” said the put-upon man. Had he seen The Life of Others, the Oscar-winning story about repression and surveillance during communism? “I know about the movie,” he said with a dismissive gesture, “but I don’t ever pay attention to Western views of the East.”

“The reunification cost us dearly,” said my niece Gabriele, a teacher in the former West Germany. “After the initial euphoria we were saddled with a solidarity tax to finance new infrastructures and reconstruction in the East. Today you can hardly tell the difference between East and West by the looks of it. But unemployment over there is still twice as high, and a divide of distrust and resentment lingers. But my second graders don’t know the difference between East and West. For them, Germany is one people.”

On October 3, Germany celebrated a Day of Unity for the 20th time. To highlight the event, a 21-foot girl puppet marched through Berlin’s downtown to meet her 45-foot uncle in the city’s center (www.riesen-in-berlin.de). “Separation and reunion” was the theme of this giant fairy tale. Millions lined the puppets’ mile-long journey and cheered wildly when they tenderly embraced at the Brandenburg Gate, the symbol of Germany’s destiny. The giants’ hug was manipulated by cranes and wires, but the spectators’ enthusiasm seemed genuine.