My Sister Beate

©2012 Valerie Kreutzer

She got her name from the doctor who had urged our mother to abort the fetus. Rose Kreutzer had a serious kidney infection and was well advanced in her pregnancy. He had to get in there with his knife and cut deeply, it would likely injure the unborn, he said. “The baby goes, I go,” said our mother, according to family lore.

And so he cut. I remember our mother’s big scar; saw it in the morning when she got out of her nightgown, always modestly with her back to me. “What’s that fold on your back,” I once asked her. “That’s from my kidney operation,” she said matter-of-fact, omitting the drama of that scar.

“If this child survives intact,” the doctor had said, “we will call her Beate, the lucky one.”

And so she was Beate, the lucky one. She was Karl and Rose’s first child, born in 1926 in Budapest, Hungary, where Karl ministered to a German-speaking congregation, his first parish in a 40-year career.

Yes, she felt lucky and optimistic, excitable, and with energy for a whole battalion. But there was also an undercurrent of anxiety perhaps due to the pre-natal trauma, a knife so close to the placenta under an anesthetic that knocked them both out on their mother-daughter venture.

During childhood illnesses, our mother reported, she couldn’t leave Beate’s bedside. “Mutti, Mutti,” she would call day and night during bouts with measles and whooping cough. Up and about, she was often restless and fidgety. “You’re going to sit on this chair for the next 15 minutes,” Mutti would advise, setting a clock on the table. “Look at Claudia who sits quietly,” she’d say. Claudia, the third daughter and an observer, remembers these scenes.

Restlessness aside, Beate was a force to be reckoned with: the cheerleader who fired us up and on, the girl who knew how to get around the rules, the student with lousy grades and the biggest entourage of friends, the person who could be confrontational when necessary, and talk her opponent into the ground. She easily climbed soap boxes to air her views, but when someone suggested why not enter politics with all your fiery and fierce convictions, she’d always dismiss the suggestion: “Dazu fehlt mir das Nervenkostuem (I don’t have the emotional corset for that).”

Beate was a toddler when the family transferred to Berlin, Germany. I met her there when she was 11, the boss of her two younger sisters. Claudia, five at my birth, remembers our mother bringing me home after a week at the hospital—that’s how long women were allowed to recover in those days. Mutti let everyone have a peek at the new sister. “I want to hold and hug her,” Beate enthused. “No way,” said my mother who believed in the germ theory. “Go and hug a table leg instead.”

Our mother was in the first generations that benefitted from Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis’s research proving that many women died at childbirth because of unsanitary conditions in hospitals and delivery rooms. Mutti was adamant about cleanliness and used disinfectants in the wash bowl when she attended to any of us sick. And so she kept me swaddled away at least for the first few weeks, though I’m sure I got a healthy introduction to germs pretty early, not just from Beate who, as it turned out, wasn’t that keen on the nurturing role of older sister.

That role fell to Heidi, nine years older than I, who soon learned to bathe and diaper me. “I can rely on Heidi to take care of our little one,” our mother would brag to the other mother she had met at the Humboldthain, the nearby park to which she took us daily for a breath of fresh air. The mothers exchanged stories about childbirth sotto voce, while Heidi eavesdropped nearby.

Heidi was devoted to me and with her in-born sense for beauty soon decided with satisfaction that I was the cuter of the two babies. However, I was lying in the old-fashioned well-worn pram, high up on big wheels, while the ugly baby lay in a chic pram with fashionably lower wheels. The packaging turned crucial when a classmate asked Heidi which of the two babies was hers. “That one,” said Heidi, pointing to the modern vehicle. Afterwards she felt awful, as she recently confessed. We had a good laugh and commiserated on the downside of her need for aesthetics and beauty.

There’s another story involving me in a pram. The old one was left in Berlin when we moved to Schneidemuehl in Pomerania when I was six months old. So my sisters put me into a doll’s pram, a modern kind with small wheels, but clearly too small for me. One time they parked me on the sidewalk while playing Voelkerball on Handtkestrasse. In the heat of the game they forgot about me, until the pram made a summersault and I lay crying on the pavement. The team rushed over and stifled my screams with some pillows, but not before Mutti leaned out of the kitchen window and demanded to know what’s going on. “Nothing,” said my chastened sisters. Apparently there was no blood and I was soon appeased.

I see Beate as the organizer of these games, as the girl who would belittle a scrape or a fall—come on, get over it! She was not the motherly type, probably had been recruited too early to be the more mature, indulgent sister, even when she didn’t feel like it. Like when she was two and found her newborn sister Heidi in her bed. “Meine Bett (my bed),” she protested when our dad took her to meet the new addition to the growing family. Our mother had not expected to deliver her second child at home and was speechless when Heidi arrived so quickly. Beate was chagrined when they put the new baby into her crib. But as the sisters grew, they became best friends. When they fought and argued, Mutti made them stand in separate corners by the piano and before long they whispered their regrets to each other through the crack, declaring Mutti their true enemy.

Beate and Heidi were a tight team, also because our mother insisted on it. Bubbly Beate, the extrovert, made friends easily and when invitations for birthday parties arrived, Mutti mandated that she could accept only if her little sister was included. Mutti believed in safety of numbers, especially if invitations extended beyond the parish circle. “Yes, I want to come but I have to bring my little sister,” Beate had to say, secretly resenting the caveat. Heidi, sweet and meek, was really no bother, and off they went together to sometimes less than perfect homes in the lower-class neighborhood of Berlin Wedding. Beate was eager to blend in. She noticed, for example, that her classmates brought their snacks wrapped in newspaper and demanded that our horrified mother provide the same.

When she was five, our mother decided to send Beate to Hungary for the summer to learn Hungarian. Mutti thought her little girl safe at a Methodist retreat center for deaconesses that also accommodated a few children. But Beate became miserably homesick and didn’t care to pick up a new language. She befriended a little Hungarian girl and enticed her to run away. They actually took off but got only as far as the park hedges. When the retreat center unexpectedly closed, Beate was put on yet another train to spend the rest of the summer with the grandparents in Yugoslavia. She remembers arriving on the deserted train station of Novi Vrbas, sitting on her suitcase waiting. Our grandfather eventually appeared on a bicycle to retrieve her. “How could you do this to me?” she demanded of Mutti years later. “I just wanted to be able to speak Hungarian with you,” our mother meekly explained. Mutti loved Hungarian and whenever she took us to spend the summer with her family in Yugoslavia, we stopped in Budapest where Mutti laughed and chatted with old friends and turned into this foreign persona. She taught us to say “nem tudoc magyarul (I don’t speak Hungarian)”—and that was just about the extent of it. Mutti’s final attempt to get Hungarian going in Berlin faltered after Lia, the 16-year-old Hungarian niece who came to stay with us, started speaking German-Hungarian mishmash with her younger cousins. So, while Mutti gave up raising bi-lingual children, Beate carried away a childhood trauma of abandonment in a foreign land. It stayed with her to the end.

By the time I was born, Beate was eleven, Heidi nine, and Claudia almost six. I had just missed the drama of Beate quitting piano lessons. Our parents were keen on musical training. We could carry a tune before we could talk, learned to read music via the recorder at six, and hit the piano at ten. It worked beautifully for Heidi, less so for Claudia and me, and definitely not for Beate. She didn’t practice the piano, despite scolding and threats. “As long as you life in this house,” Mutti insisted, “you practice the piano.” “Then I’m going to marry at 15,” Beate countered. And that’s when our mother gave up. “I wish she hadn’t,” Beate lamented much, much later, when she painstakingly practiced chorals and tunes from Bach’s notebook for his Anna Magdalena.

Younger sister Heidi practiced her scales and quickly advanced to the organ, becoming our church organist at 14. That responsibility weighed heavily on her. On Sunday mornings she sat with stage fright at the breakfast table, unable to eat that warm bun, our Sunday treat. “I’ll have it since you can’t,” Beate would say, reaching for Heidi’s Broetchen with brazen nonchalance.

Farewell to Berlin

In the summer of 1937 we moved from the Ruegener Strasse in Berlin to bucolic Schneidemuehl in Pomerania (now part of Poland). My baptism shortly after our arrival was an event. Mutti had sewn long gowns for her girls and the family presented a lovely tableau before the altar. Mutti told me that Papa choked and shed a tear when he baptized me and all my life I believed that Papa, yearning for a son, had cried with disappointment over yet another girl. But during one of my visits with Beate in Frankfurt when I was already retired, Beate set me straight on Papa’s tears. “He choked because he was so moved baptizing his own little baby,” she explained. “That’s what happens to fathers.” She knew. Her Werner had baptized their two girls. Her explanation was a revelation. All my life I had carried a grudge. It finally melted away.

My earliest memories of Beate are foggy. She was in cahoots with Mutti, they were a united front, with Mutti the more lenient and flexible. I was about five when I had a major run-in with Beate. I asked for a piece of bread with jam right after the dishes for the Mittagessen, the main noon meal, had been done. Mutti usually cut the bread and spread the jam for me and I would take off for the garden to play away the afternoon with friends. But that one time Beate put down her foot, hands framing her hips. “We’ve just finished Mittagessen,” she said. “No snacks until five.” Mutti, about to cut the bread, nodded her agreement. Choking back tears, I headed for the garden and climbed the stone pillar by the fence. That’s where I spent the afternoon, watching the big dial of the cathedral clock creeping ever so slowly towards five. As soon as the bell chimed, I was in the kitchen, getting my snack.

That episode taught me an important lesson about deferred gratification. Because on the second day I didn’t anxiously wait for the stroke of five, and on the third day I was surprised when the bell rang and I had almost forgotten about my snack. What I learned at five came in handy when I saved for a down-payment for my first home or weaned myself from cigarettes.

Much later Beate told me that she had many discussions with Mutti about my upbringing. Too much pampering, Beate would complain. “If I now know better,” Mutti would say in her defense, “let me practice my new insights.”

My sister Heidi loved me dearly—despite that early pram betrayal—and indulged me a lot. She told me stories and I insisted on at least one a day. And when Heidi ran out of fairy tales and myths, she invented stories, often with some tragedy befalling doomed lovers. We had a book of German folksongs—Der Erksche Liederschatz—with romantic, art nouveau illustrations and Heidi would often use pictures as blueprints for her tales. There was a drawing of a damsel on a cliff with her lover below trying to pick a flower. As he lost his foothold and went down, he cried: “Forget-me-not.” And that’s where the flower with its tiny blue petals got its name, Heidi explained.

She also let me sleep with her. She had her own bedroom in my earliest memories. I was still sleeping in the Kinderbett in my parents’ bedroom. Claudia and Beate shared the bedroom upstairs. Heidi’s room was small, painted blue, and exuded order. Everything had its place; her socks, lined up in the chest of drawers, had little blue crosses to identify the owner. On laundry day—a once-a-month mega affair—there were dozens of socks from four girls on the line, but Heidi’s could be easily identified by their blue crosses. “The crosses were Mutti’s idea, because Beate always helped herself to mine. ‘Then mark them,’ Mutti had said,” Heidi recalls.

I liked being with Heidi in that blue room and once in a while she let me sleep with her, always complaining in the morning that I took up too much space.

I couldn’t help it because the mattress on a sagging frame made you roll towards the middle, too tight for two. “I’ll make myself as thin as a little thread,” I promised, only to be told in the morning that I had turned into a fat lump again. Still, Heidi indulged me.

Her blue room often changed function and occupancy. At one point it was Claudia’s and my room; during the later war years when coal became scarce, the beds went out and a table with six chairs moved in to become the only heated room when temperatures sank below zero and the rest of the house turned icy.

I had a little table and chair next to the tiled stove in the corner and was making some Christmas cards when I got into an argument with Beate, sitting at the big table. It was 1943 and I was in first grade. At school we had been told that Christmas was about Santa Claus. At home we talked about the birth of Jesus. Only one story could be true, I said to Beate. “At Christmas we celebrate the birth of Jesus,” Beate said authoritatively. That seemed to be a minority viewpoint and I preferred to go with the flow. “No,” I ventured, “I believe it’s about Santa Claus.” “Nonsense,” said Beate, “it’s about Jesus!” We argued back and forth “it’s Santa Claus,” and “no, Jesus” until my oldest sister got so fed-up with me that she got up and exited the room slamming the door for added emphasis. I sat there dumbfounded, wondering what’s what. In our household we rarely exchanged ideas or listened to other viewpoints. You better believed this and that, and if you didn’t, a banged door could shut you up and out.

Beate was good at spouting opinions and often ruled the roost. I remember a scary night when she and Heidi fought over a featherbed. They were sleeping in the upstairs room in matrimonial beds at the time and for some reason there was only one featherbed. Heidi said it was hers. No, it was hers, said Beate. I lay between them because I had persuaded Heidi to let me sleep with her. I watched in horror as they tore the featherbed, soon lashing out at each other. I hoped Heidi would win, but then she let go. Beate turned her back on us and disappeared under the warm cover. Heidi tucked me into her lap; we lay quietly, getting cold. “Go and sleep with Beate,” Heidi whispered. I felt torn, but after a while I crawled in with Beate, feeling like a traitor. What a surprise to find Heidi the next morning snug under her own cover. “Mutti came home and brought the missing Federbett,” Heidi explained.

A few years ago when I moved into my vertical home in Seattle, Beate—who had become my surrogate mother by then—insisted on giving me a house warming gift. “Well, a warm comforter would be nice,” I said. She eagerly opened her purse and dished out Euros. Back home in Seattle I bought the warmest comforter from Bed Bath & Beyond. When I now snuggle under it in the deep winter by the open balcony door I think of my oldest sister with special affection. Sometimes I wonder whether she ever remembered the featherbed fight. In her adult years she didn’t care to be reminded of her youthful escapades and domineering ways. By then she would have given you the shirt off her back; by then she was forever supporting good causes despite her modest means. “I lived it up in my youth,” she’d say. And that was that. She lived without apologies and had a rare talent to forgive herself past transgressions, doing good in the present wherever she could.

At school she was a lackluster student at best. She always started with high hopes. “Mutti, today I did great in the exam, an A for sure,” she would boast charging into the kitchen. By next day she allowed that it might be a B. And when she got a C or even less, she said, “Perhaps next time.” Meanwhile, Heidi, a conscientious and diligent student, brought home the As, with Beate announcing the feat gleefully as if she’d been the achiever. “I only studied what interested me,” she reflected as an adult. And most of the traditional curriculum, it turned out, didn’t interest her. She loved biology, knew hundreds of plants by their names and habits, spent hours in the woods collecting mushrooms, berries, and other edibles and helped us survive during the months of starvation in Berlin after the war.

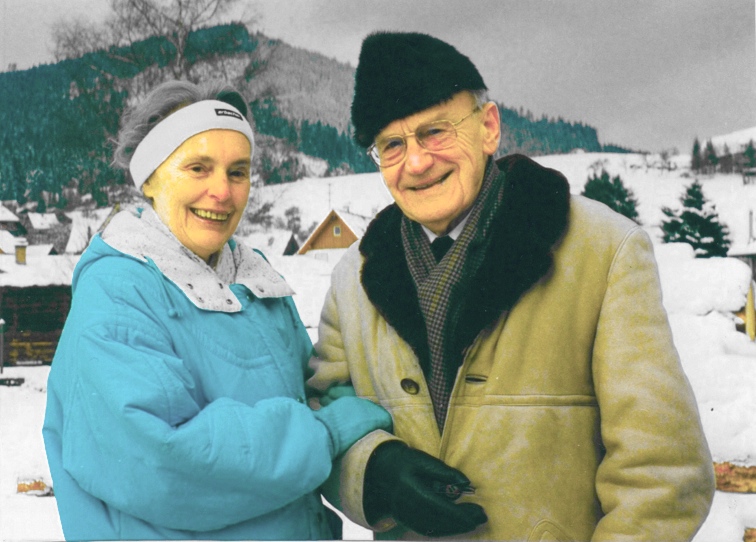

When I visited her during her golden years in the Black Forest and it was fall, we always went mushroom hunting. We’d get lost among the tall pine trees in our slow and meditative search, but when we found some perfect specimen we yelled with joy, alerting each other. She always insisted that I had the better instincts, told everyone about my mega finds, just the way she liked to brag about the smart and talented members in her clan without the slightest hint of jealousy.

Mutti and Papa were rather exasperated with her poor performance at school. In one of the episodes of family lore, Papa caught Beate painting her fingernails, an extravagance in our puritanical household. “Lakier dir lieber dein Gehirn,” he admonished. “Shellac your brain instead!” became a family bon mot.

In French she never studied her vocabulary or grammar, but when she had to memorize La cigale et le fourmi, a famous fable about the reckless grasshopper and the diligent ant, Beate absorbed the poem with perfect diction. Whenever higher-ups visited her classroom or she was about to flunk, Beate managed to shine with her fluent recitation. Eleven years later when my turn came to memorize La cigale… I already knew it by heart.

Beate had fierce loyalties towards the family and Mutti could count on her in all matters of the household, be it harvesting vegetables in the garden, canning, cooking holiday meals, organizing bazaars, or decorating the church. In my eyes they were in cahoots, at times against me. Like the time we were trying to find a new pair of shoes for me. The wartime shops were bare, nothing fit. There was that patent leather pair I was dying to have. I curled my toes to make them fit. But Mutti demanded to see my foot under that x-ray machine in the corner and looking through the viewer decided that the shoes were way too small. The end--but not for my yearning, disappointed heart. Wailing and crying I followed behind as we headed home, Mutti and Beate up front with linked arms. A neighbor, the friendly director of a boys school, came out of his villa to inquire about my woes. I told him. He was so sorry, he said meekly.

Just as they were about to turn the corner of Bismarckstrasse and enter our house, Mutti turned around and said: “If I am such a bad mother, why don’t you find yourself a better one.” And then they disappeared. I wondered whether Beate had inspired this directive. What to do? It was evening and I wandered across the street to the row houses where the mother of a boy I knew was working over the kitchen sink by the window. The bare bulb at the ceiling cast a halo around her blond curls. She looked nice enough. Should I ask her to be my mother? In the end I lacked the courage to knock on her door. Instead, I sneaked into the house and slid under our parents’ bed, settling amidst dust balls and a suitcase. I watched feet coming and going until Mutti’s black heels stopped next to the bed. She bent down and grabbing one of my ankles and slid me out from under. “So you couldn’t find yourself a better mother?” she inquired smugly. Choking back tears I shook my head in defeat. Luckily she didn’t dwell on my humiliation and let me quietly return to the lap of family life. It was suppertime, the table was set.

I don’t think I ever got a new pair of shoes because there were none to be had. All resources went into the war effort. I usually wore my sisters’ hand-me-downs, and while clothes could be patched and altered, shoes were often beyond mending. A grouchy shoemaker always made a fuss over our downtrodden footwear, eventually accepting them “for the very last time.” Visiting the man was one of the odious chores that fell to Claudia and me, hoping that our curly cuteness would mellow the old man. He lived near Tante Schuetz, a parishioner, and we usually rang her apartment bell on our return, especially in the winter with sub-zero temperatures, when we could defrost next to her warm tiled stove. Tante Schuetz usually had a treat for us. A professional seamstress, she quickly pulled out needle and threat to darn holes in our mittens, mend tears in tomboy Claudia’s dresses, or attach loose and missing buttons. She was super neat and organized and her modest apartment felt like an oasis compared to our home of creative chaos. Little did we know then that Tante Schuetz would soon become an in-law, thanks to Beate.

During her teens I remember Beate as a whirl-wind. She helped herself to what she needed, including Heidi’s neatly marked and mended socks, and dismissed scenes of “you did it again” without apology. Her favorite song was Lustig ist das Zigeunerleben, trallala, lala, la…(Merry is the gypsy life…). She was always surrounded by an entourage of adoring friends who loved her cheerleading, storytelling, and chutzpah, and in return could count on her loyalty.

She was a non-conformist and only joined what suited her. Hitler youth groups didn’t. She went once on a Thursday and then quit. When school officials asked when she had last attended, she’d say Thursday. At the dinner table she bragged about her white lie and Papa laughed with approval. A girl after his heart!

She was different. She also smelled different. I figure that she was menstruating by the time I became aware of her. Story goes that Beate was in denial for the longest time, still running around in Haengerchen, little girl shifts without room for breasts, when, in fact, hers were straining the fabric. It’s perhaps typical of early bloomers that they have difficulty being the first in their age group menstruating and sprouting breasts—I know that from Maria who started menstruating at nine-and-a-half. Beate, I understand, didn’t like what was happening to her body, but eventually she made the most of it, enjoying her attractiveness to boys, flirting dangerously under Papa’s watchful, nay, wrathful eyes. At the end of her life, when she was confused in the present, she remembered her youthful escapades clearly, as our sister Heidi reported.

On a school excursion to Kiel, for example, her class of girls met some boys and secretly organized a get-together with music from a gramophone. Frau Mellin, her teacher got wind of it and brutally interrupted the fun and frolic with “our boys are fighting in Russia and you are dancing!” One of the young men in the group was smitten with Beate and, since he didn’t even know her name, wrote a letter “to the girl with the broken shoe buckle.” They secretly corresponded. Then there was Heinz Radner whose father was a criminal investigator. For little rendezvous Heinz turned up with his shepherd dog, later joined the SS but survived the war.

In an effort to placate her younger sister, Beate recruited Rudi Spieker, the son of the delicatessen shop on prominent Posener street, to become Heidi’s boyfriend.

And then there was Martin Erdmann, the young man sitting next to Beate at a wedding. They corresponded until Papa found out and put a stop to it.

I got a whiff of Papa’s wrath one Christmas when we all attended Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel. During intermission a boy greeted my oldest sister with a casual “Hello, Beate.” Papa slapped him right then and there for this brazen familiarity. Beate was mortified, and Mutti urged Papa to apologize.

To me, the young woman Beate belonged onto another planet. She had underarm hair, ate with enormous gusto, gaining by the pounds while bursting through the seams. When she was drafted to harvest potatoes in the country, she borrowed Papa’s pin-striped pants and then couldn’t zip them over her curvy hips. I still see her standing next to the dining table, giving us a demonstration how she held those slender pants together under her skirt—in those days girls wore skirts over pants. She had just wolfed down eight Palatschinken—crepes filled with crème fresh or jam—and Papa’s pants were about to split, ha-ha-ha, she bent over laughing, as we all joined in the hilarity of the sight. One of those Beate moments, outrageous and loveable, what would we do without her? She told us how she had skipped ahead of the line that day to catch the train home, leaving most of the girls in her brigade in the dust. “They were livid when I raced to the top of the line and jumped on the train,” she reported with glee. Even Papa laughed at Beate’s daring; we all admired her and were glad that she had made it home on time while the others were still waiting for a train. “What a girl,” was the undercurrent of our reluctant admiration.

And then Beate received a letter drafting her into the army as Flackhelferin, assisting in the early warning system. No more school, away from home at 17. “Oh no,” Mutti cried, “I’ll go and you stay.” Without Beate’s activist help with harvesting, canning, and cooking—all the while keeping up a lively chatter--our mother felt done in by the burden of household, garden, and parish. But, of course, Beate went, not tearfully, as I recall, but with a sense of importance and adventure. By then she was in love with Werner and almost engaged.

I was six when that happened and it seemed that the whole world started turning around that event. The story goes that Werner and Beate met at the Christmas church bazaar. They must have seen each other before, but Beate hadn’t noticed the young man. He later recalled admiring the picture-perfect family on the Sunday Papa commenced his ministry in Schneidemuehl: the girls all dressed in ruffles of pink and beige, and I, the six-month-old baby in Mutti’s arms. Six years later, the pretty oldest daughter had blossomed into a curvy, classic beauty, sizing up the dashing young officer on home leave, probably the only eligible Christian young man in a radius of miles.

Beate had been asked to move that church bench over there when Werner stepped forward with “gnaediges Fraeulein, (young lady) please let me help you.” And I imagine her blushing to her roots and going a bit limp as they carried the bench together, not knowing that they’d end up moving lots of church benches in their later life as pastor and wife. They were smitten right then and there.

Little would have come of the bench incident, if not Papa, ultimate patriarch who ruled his harem with iron rules of chastity, had not said to Werner’s parents in a moment of jovial merriment, “wouldn’t that be something, your son and my daughter… ha-ha-ha…” The Schuetzes were pillars of the dwindling war-time congregation, Herr Schuetz a railroad employee, Frau Schuetz a seamstress, not quite the match for my class-conscious parents. But the Schuetzes thought that their golden boy was good enough for a princess, and hadn’t Pastor Kreutzer hinted at a possible union? So, when Werner confessed before leaving again for the frontlines, that he was in love the Schuetzes invited our parents for dinner. And over clanking knives and forks, Werner’s mother reiterated Papa’s idea, “how about our son and your daughter” without the added ha-ha-ha. Papa was furious. He slammed down his utensils, demanded coat and hat and raced out of the apartment, with Mutti, humiliated and in tears, trailing 10 paces behind. She must have prevailed because I remember some love letter writing sessions after Werner had obtained permission to correspond with Beate.

Whenever she received one of Werner’s letters, she became very nice to everyone, didn’t even argue much or slam the doors. The world whirled around her and our mother gladly pitched in and helped the affair along. They were pouring over empty pages after reading Werner’s first letter and then Beate wondered with bursting heart and out of her head, how to respond. Mutti told her. Now, this is what you say—still all in formal “Sie” address. I don’t think Werner ever knew that the first letters he ripped open with a pounding heart had been written by his mother-in-law with whom he had life-long issues. I think my mother loved writing them, just as she loved sewing Beate’s engagement dress made of two remnants, grey and black, with appliqué flowers and embroidery hugging the bosom, immortalized in the photographer’s engagement photo. But first there was a lengthy courtship protocol, sternly dictated by Papa who seemed to give in to the inevitable.

Once it had become clear that the two were in love, Werner was invited to meet the assembled family in the blue salon. There were rituals to such gatherings with us performing and singing around the piano where Heidi held forth. Once we had been dismissed, Werner was alone with Papa and the two men launched into war stories. Papa had served as a skinny eighteen-year-old during World War I, fighting on the Italian front, stuck in ditches high up in the Dolomites. Every time the Italians tried to rush the mountain, they were mowed down by the Austrians. So the Italians tried to undermine the mountain and blow it up. For months the Austrians listened nervously to the continuing noise of drilling; when it stopped they held their breath, awaiting the explosion. Papa, shell-shocked, was evacuated shortly before Col di Lana, his mountain, blew apart, killing hundreds of soldiers. Papa recovered at a military hospital and photos of the time show him pale and gaunt in a uniform that seemed way too big.

Now Werner, on the other hand, filled out his uniform perfectly, proudly sporting the stripes and medals of a young captain. His mother had helped him look his best by brushing the grey woolen jacket and cleaning with a little bit of gasoline—that’s how you cleaned woolens in those days—and to get rid of the smell, Werner dabbed the outfit with some precious Au de Cologne, and oops, poured out half the bottle. Great panic. Though he would be walking for 30 minutes to our house over the Kuedow Bridge, it wasn’t long enough to get rid of the smell, he was afraid. His mother got out the iron to steam the uniform, waving it this way and that, but then it was time to leave and Werner gritted his teeth as he set out. I don’t think anyone noticed his arrival in a cloud of perfume over gasoline.

“I just knew how to engage Papa in some war stories,” Werner later recalled of his late-night encounter. He had participated in Germany’s invasion of Poland, followed by the march into Paris. At the time of their engagement he was at the Russian front. Finally, as the clock struck eleven, Werner gathered all the courage he could muster and asked for Beate’s hand. By then his nervous, sweaty hands had made a row of braids with the golden tassels hanging from the Hungarian table cloth. Papa, having warmed to war stories and the young man, granted permission for the courtship. Since Beate was away on some ditch digging war effort, it was agreed that the two could meet in Neuruppin where Beate was stationed, with Mutti as vigilant chaperon.

The courtship was a family secret and Mutti and Beate admonished me not to breathe a word to anyone. I took that very seriously. One time our piano teacher casually mentioned Frau Schuetz and I almost panicked. Ran home and told them how dangerously close we had gotten to revealing the secret. For some reason Mutti and Beate laughed with amusement.

On the day the engagement was announced on printed cards, the couple promenaded arm-in-arm along the Posener Strasse, the street to see and be seen. It was an afternoon custom to stroll along that downtown street, especially if you had someone or a thing to show off. In her early teens Beate used to “borrow” Heidi’s guitar and parade with it up and down the Posener, implying that she was the musician. Now the lovers strolled back and forth, letting the public and gossips know that they were an item.

At home we celebrated the engagement with readings from the Bible, a little speech from Papa, love songs, and the best food the meager war pantry could offer.

Engagement

We’re talking 1943. I was six and Claudia, my buddy, was 12. Werner, a single child, felt no doubt overwhelmed by the force and size of our tight-knit family. He tried his best to break into the circle. And so he suggested accompanying me to school one morning during his home leave. On some level that was flattering, on another it was awkward to have this dashing officer walk next to me for about 20 minutes, up Bismarckstrasse, through Moescha Park, and then through the neighborhood to my elementary school. I always walked alone--Claudia was already at the middle school—and part of my walk included balancing on the stone embankments of the various front yards. Werner gallantly offered his hand but I refused it, knew how to do this on my own, thank you. And so we arrived at school, earlier than usual, thanks to Werner’s passion for punctuality. We joined the other kids at the foot of the broad staircase, the doors still closed and guarded by an upper class student. The kids widened their circle around us respectfully—what now? And then the guarding student, comprehending the momentous presence of the dashing officer, waved us in, the first lieutenant and first grader, and we marched up the stairs while I felt awed by the privilege, walking very erect as I felt my school mates’ eyes on my back. In the empty classroom I settled into my desk and Werner took his leave.

Years later, after he returned from Russian imprisonment, a man almost broken but slowly mending, he accompanied me once to the ice skating rink. In those days you had to attach the skates to your boots, and I remember how Werner knelt before me offering to help me. That didn’t feel right. I could do that for myself, I informed him. We both remembered the incident, Werner full of regret. “I so wanted to do this for you,” he said wistfully. As father of two girls he later had plenty of opportunities to bundle toddlers and tighten skates.

But back to 1943 and the lovers’ first kiss under a tree in Neuruppin, with Mutti a vigilant chaperon nearby. In those days good girls had to be chaperoned lest they succumb to unfettered lust and passion; but with Mutti totally absorbed with labors of housewife and pastor’s wife, chaperoning fell to Claudia and me, and we exercised our assignment with a vengeance.

Problem was that Werner and Beate tried to outwit us and stealthily disappear. “There they are,” we would scream when we finally found them sitting entwined on a park bench. “They are kissing again,” we yelled, descending on them like Indian warriors. With a sigh the lovers moved a few inches apart, engaged us for a while in childish banter until we got tired of them and drifted off to better games, and they could resume kissing and cuddling.

Beate was the ultimate romantic. She wasn’t much of a reader in her youth but there were some novels she devoured and cried over and reread and retold with such color and fervor that I soon knew them equally well without having opened the covers.

And then there were movies that completely engrossed her. One was about Robert Koch who discovered the tubercle bacillus. Knowing the danger of contagion, he refused to kiss his young wife dying of tuberculosis. “Robert, warum gibst du mir keinen Kuss (Robert, why don’t you kiss me)?” she lamented in one of the pivotal movie scenes and Beate would enact it with appropriate drama whenever prompted.

Immensee, a movie based on a 19th century novella was another hit with Beate. I read the novella in eighth grade and per chance the pre-war-produced movie was playing in the theatre. Beate knew the script by heart but came with me to see it again anyway. My German teacher encouraged us to go and then asked students to contrast Theodor Storm’s novella with the movie. Her hidden agenda was to teach us the difference between art and kitsch. I volunteered to report on the movie. Infected by Beate’s passions, I held my audience in a firm grip, making them shudder and cry. In contrast, my classmate’s report on the novella fell flat. Afterwards we were asked to vote, and surprise, surprise, the movie—labeled kitsch by our stern German teacher—was the winner, not the nuanced, symbol-laden classic. Our teacher was crushed and never quite forgave me. When I reported at home that the movie was kitsch Beate remained unconvinced.

But back to Schneidemuehl where we had a charmed childhood despite the war.

I write this last sentence with chagrin, realizing that we lived under a blindfold.

A few years ago I taught a course on world religions to seventh graders in our Unitarian Sunday school and in the context of discussing Judaism invited Liesel Van Cleeff, a Holocaust survivor, to talk to the students. She grew up the daughter of an industrialist in Rotterdam and after the Nazis invaded, lived for a while in hiding with different farm families, until hunted down and transported to Theresienstadt in Austria. She was twelve, separated from her family, sick and near starvation, spending her days shelving boxes of ashes. She admonished the students to cherish their freedoms and work for justice in the world. She talked without bitterness. I cried listening to her story, realizing that only fate and a few hundred kilometers had separated our different worlds.

In Schneidemuehl we were lucky that the Russian bombers just passed over our town on their way to Berlin where they unloaded. Sirens would alert us of their passing and we had to descend into the cellar—always in the night—and bed down on apple crates. We got used to the routines, weren’t really afraid since our little town was no primary target. Only once in a while a stray bomb would hit, causing limited damage.

During the day Claudia and I roamed the hills of Moescha, knew all the paths and benches in the Stadtpark, and secretly acted out weddings, funerals, and baptisms during the week in the empty church with Claudia knowing all the appropriate liturgies by heart, draped in Papa’s way-too-big black robe.

At night we listened to the news, always introduced with Wagner fanfares of victory. We felt safe. Only Papa whispered that things might not be as rosy. He secretly listened to the BBC and got different information. He was in trouble with the Gestapo who came to pick him up twice, threatening that if they’d come for him a third time, he wouldn’t return home again.

Beate remembered an episode from those dark times. Every block in Schneidemuehl had an appointed watchman and informant. Ours was Herr Daluege who regularly pestered us about our torn window shades leaking light at night (the whole city was supposed to be blacked out in case of air raids), and he also reported that Papa said “Gruess Gott” instead of “Heil Hitler,” thus adding to the Nazi’s list of grievances against him. One afternoon this poorly educated man came to see Papa and said that he was supposed to write a report about him. He didn’t know what to say. “Let me have the form,” Papa said nonchalantly, inserting the questionnaire into his typewriter and typing up a glowing report about his upright citizenship. “There you go,” Papa said when finished, handing the sheet back to Herr Daluege who thanked Papa profusely.

“They are not going to get me,” Papa said after returning the second time from his nightly interrogation at the Gestapo. “I’ll disappear over the green border,” he hinted, thinking that he would be safe in his homeland, Austria. The end of the Nazi era couldn’t come soon enough for him.

We celebrated Christmas 1944 true to tradition. On Christmas Eve we bathed and wore our Sunday best, sang all the verses of Silent Night and Oh, du froehliche, and listened to the story Papa read from Luke. For once all Kacheloefen (tiled corner stoves) radiated heat, and the French doors between the dining room, salon, and study were wide open. There were presents under the tree, including a package from Tante Sophie in Vienna will all sorts of exotic things, including a dark blue silk scarf. Papa distributed the items at random, but I wanted the silk scarf and started sulking loudly, not really my style. I remember Papa kneeling down before me, holding out the scarf, “Here, it’s yours.” Secretly I made a note that sulking loudly gets you what you want. Though in the coming years of homelessness, mortal fear, and hunger I didn’t get a chance to practice my new insight.

The week after Christmas life around us seemed to crumble. Beate, on home leave, returned to the front to help shoot down Russian bombers. Mutti was beginning to lament that we’ll all end up in Siberia. For some reason she decided to do the mega laundry and since it could not dry in the freezing attic, she spread sheets and underwear over the stoves and furniture, even in the sacred blue salon. Meals were haphazard, although the cellar was stocked with enough fuel and food to last us for half a year. Despite the sense of doom and departure, we were still scrounging in our savings mode. Our lonely rabbit hopped around the mountain of coals and wood in the basement, and the canned fruit and vegetables, the 100 eggs preserved in some solution, remained untouched on the shelves. “Let’s save that for Beate’s wedding,” had been the motto for almost a year. That wedding was to be the ultimate feast and family celebration.

Papa had secured a ticket to a conference in Berlin and was packing his little suitcase. He was to take me, the youngest, with him to Berlin. I was to stay with Tante Benthlin, a parishioner who had sought refuge with a sister in a Berlin suburb. Mutti who was preparing for doomsday, put the family silver into Papa’s suitcase. He removed it, replaced it with apples from the cellar because he was sure he’d be back within a week. (I have inherited the family silver because Claudia rescued it in her suitcase. “I hardly had any clothes to pack,” she remembers with a shrug. “So I got the silver.”)

It was a bitter cold morning when we set out to the train station crowded with refugees from the Ukraine, now stranded in Schneidemuehl. Civilian traffic had come to a standstill. The only trains passing through were filled with wounded and dying soldiers returning from the battle field, and young boys and ammunition riding to the front. Heidi, 16, had come with us and we hung around the station for most of day, hoping for a train. At one point, Papa took Heidi aside and told her in a whisper that the thunder we could hear in the distance was the Russian front. “You, Claudia and Mutti have to get out as soon as possible,” he urged Heidi. He expected Heidi to act as the adult because Mutti was a bundle of nerves and would soon retreat to bed with one of her violent gall stone attacks.

We returned home at the end of that futile day at the station and started out again the next morning. It had snowed that night and we loaded the suitcases onto the toboggan. When we passed the yellow letter box at the corner it had a pretty white snowcap. I looked at it and thought, “This is it. I won’t ever see that box again.” That moment marked the end of my childhood. I was seven. From then on I had to take care of myself and act like a grownup. Schneidemuehl was passé and thereafter became a family reference of paradise lost. “Remember Schneidemuehl…” someone would say and get us dreaming of swims in crystal clear lakes, berries and mushrooms in the woods, games and rivalries, and birthday, Easter and Christmas rituals. Schneidemuehl meant the six of us and as we lost our home and all possessions and as Beate, Heidi, and Claudia left one by one, home and family life became fractured and changed forever. Schneidemuehl, now part of Poland, became a place of no return.

During my stay with Tante Benthlin in a Berlin suburb I worried about the rest of the family. I wondered whether Mutti, Heidi, and Claudia had gotten out of Schneidemuehl, and also worried about Beate at the front. I had an address for her and wrote her a letter. “I am doing o.k. here,” I wrote, “but we spend most of the nights in the basement with bombs falling left and right. I hope you will be alright and God will take care of us.” I remember feeling teary as I wrote and a bit queasy about citing God. Tante Benthlin gave me a stamp and I handed my letter to her sister for posting. “We will not burden the postal service with your childish letter,” she said categorically. “They have more important mail to deliver.” Tante Benthlin’s relatives who had kindly taken us in were more supportive of the Nazi regime, I noticed, and I knew enough to keep my mouth shut. I was growing up fast. On Feb. 7, 1945, I turned eight and celebrated my birthday for the first time without my family. I dimly recall an ersatz-birthday cake and Papa came to visit from the inner city where he stayed at a Methodist hospital. I took him to the train station in the evening and held his leather-gloved hand. “Now the oldest and the littlest of the family are together,” I said. “Yes,” he countered, and then paused. “You know,” he said, “these people are very kind to you and you shouldn’t talk so much about Mutti and your sisters.” I nodded with a lump in my throat.

And then one day when I was outside playing with some neighborhood children, Mutti in her raccoon fur jacket came down the street. I ran towards her screaming and we hugged tightly. I sobbed for a long time tears of pent-up emotion.

Mutti took me with her to Seusslitz in Saxony where she and Heidi and Claudia had ended up after their harrowing escape from the Russian front. After sleeping on straw for a few nights, Mutti offered to pay for a room in the modest hotel, crowded with refugees and officers on short furloughs. There was a piano in the dining room and Heidi, an accomplished pianist, started playing Beethoven and Chopin on the long evenings with nothing to do. She always ended with the lullaby Schlafe, mein Prinzchen, schlaf ein… She sang along in her high and clear soprano, indulging in curlicues of the right hand. And as she sang, conversation stopped next-door where the officers ate their supper. Heidi was our pretty princess who offered moments of escape from a dreary reality framed by doomsday fears.

And Beate at the Russian front? I don’t really know what she did, but it had to do with surveillance of bombers coming from the east. I imagine some German artillery pointing skyward to fire at bombers droning through the night sky towards Berlin. My 18-year-old sister was supposed to shoot them down while housed in an iced-over shack. Beate was good at cooking, canning, singing, telling stories, laughing out loud, believing that life was a bowl of cherries. So it came as no surprise that she went AWOL at the end of her next brief leave. She took the train to Berlin where she knew Papa was, mindful of hiding her uniform under the winter coat Mutti had tailored from a blue and brown checkered woolen blanket. That coat had leather trimming around the collar and pockets, one of Mutti’s ingenious master pieces. Not owning another pair of shoes, her army boots were a potential give-away, but Beate managed to hide them deep under her seat, especially during frequent stops when armed soldiers were looking for defectors. If found, they were shot point blank.

Never the sanguine type, Beate was a bundle of raw nerves by the time she found Papa at the Bethesda Hospital in Berlin-Steglitz. Papa decided that she must join the rest of the family in Annaberg, Saxony, where Mutti, Heidi, Claudia and I had fled when the Russian front was about to reach Seusslitz. Trains were infrequent, tickets impossible to obtain. In those days, train stations had men sitting in little booths clipping tickets that allowed you onto the platform. Even if you just accompanied a friend to the train, you had to buy a pass for 20 Pfennig. Here’s the plan, Papa explained to Beate. You get that platform pass and I’ll be loaded with your suitcase and bags, telling the guy in the booth “just a minute,” implying that I need to unload before giving him my train ticket. I don’t know whether they practiced the caper but in the end Papa charged past the booth and quickly disappeared in the multitudes that crowded the station. Beate followed with her Bahnsteigkarte. Papa had chutzpah and Beate was his best student. She arrived unscathed in Annaberg were we were quite safe because Germany had capitulated before the Russian tanks moved into the town square.

From where we were staying at Tante Anneliese’s house, we could look down on the square, surrounded by the town hall and apartment houses, all decked out with white bed sheets—the sign of capitulation. Annaberg was the last town the Russians conquered and they arrived ebullient and satiated with victory. While we were prepared for their arrival, Mutti kept saying for weeks, “I hope the Americans will get here first.” She harbored a soft spot for the Americans dating back to her days at the American mission school in Macedonia where she had learned English overnight and with already three other languages under her belt soon became the interpreter for the school’s president. She loved the Americans for their friendly interaction with students, their camaraderie, playfulness, flexibility, and lavish encouragement--so very different from the authoritarian teaching she’d experienced in public schools in Yugoslavia and Hungary. Mutti yearned for American occupation and dreaded the Russians now entering on top of their tank convoys waving the red hammer-and-sickle flag. Knowing their record of looting and raping, Mutti decided that we must not sleep in our beds in the house and so we moved at night into abandoned old silver mines; the one nearby had at least 20 inches of standing water. People had sought refuge in them during the bombing raids of the final days of the war and had put down wooden planks over stones. We gingerly balanced along the planks to settle into the dark and wet nooks of the caves. I slept soundly, but according to whispered stories during the day the nights were punctuated by shooting and screams from women being raped in the nearby town. For fear of being found, Mutti decided that we should sleep in different locations every night. I remember bedding down on the benches in the church on alternate nights, but as the Russians tightened their control a semblance of order emerged and eventually we returned to our beds. Every day there was a new proclamation how citizens were to comply: Bring in all your radios, bring in your clocks, anything of value was collected and shipped off to Russia. Worst of all, all food supply lines had broken down and shops were empty.

We got one loaf of bread per person per week. I remember the loaves all lined up on the kitchen cabinet. Claudia had the ingenious idea of carving little marks for every day into the crust; and then she added also an M for Montag (Monday), D for Dienstag (Tuesday) and so on, indulging in the pleasure of eating the little bits of carved crust. We were so very hungry. I followed Claudia’s example but on Mittwoch (Wednesday) my little finger couldn’t stop digging deeper. So when Wednesday arrived, there was nothing but the rind. Mutti was aghast and I felt deeply ashamed of my weakness and greed. After praying the Lord’s Prayer the next time I asked Mutti, “And lead us not into temptation, is that about not digging your finger into the bread?”

“Als Gott wuetend war, schuf er das Erzgebirge (When God was furious he created the Erzgebirge),” Beate pronounced with Biblical authority. The Erzgebirge, a mountainous area near the Czech border, was rocky with poor soil, its single claim to fame were handicrafts of lace and wooden figurines. In June of 1945, the shelves in the grocery stores were empty and the highways clogged with thousands of dispirited refugees who kept walking aimlessly. The residents of Annaberg and the Erzgebirge were reticent at best and now downright hostile in the face of this humanitarian disaster.

We were so lucky to stay with Tante Anneliese, who had been in the youth fellowship in Budapest, Karl Kreutzer’s first parish. She knew Beate as a baby, and though childless herself, extended great kindness to all of us. Tante Anneliese was married to a Methodist minister with a Ph.D. in Egyptology. He had been drafted and was fighting somewhere. In his infrequent letters he let Tante Anneliese know where he was through encrypted messages—a fact that fascinated us endlessly. Without any communication during the after-war chaos, Tante Anneliese didn’t know where her husband was and whether he was alive, just as we didn’t know whether Papa had survived at the Bethany Hospital in Berlin, and Werner at the Russian front.

I can’t remember being worried about the fate of the adults, I was consumed by hunger. Mutti said to stay in bed to save energy and we did. I wasn’t much of a reader at eight, but Beate, Heidi, and Claudia curled up with books from Tante Anneliese’s bookshelves. Heidi complained that just about every book talks about food. What really galled her were stories of poor little Haenschen who had nothing but a crust of stale bread. Oh, how we wished for a crust of stale bread! I remember once playing with the custodian’s little girl and fainting in the sandbox. Her mother took pity and gave me a piece of bread spread with mashed potatoes—I couldn’t believe my good fortune, bread and potatoes! That family, like most locals, had hidden resources and country connections. We had nothing.

When nettles sprouted in the wild, we went out to cut them down and cooked them, once in a while grating a potato into the mush for thickening. Mutti, remembering her country roots, had the idea of cutting out the eyes of a potato and stick them into the dirt on the south side of the parish. Maybe they would sprout and in the fall, if we were still alive, we could harvest new potatoes. We left Annaberg before harvesting time but Tante Anneliese later reported that the eyes did produce clusters of potatoes.

Hunger is a humiliating obsession. You can’t think of anything but how to get food. We’d go to town and comb the shops with their empty shelves. One time Beate and I discovered a mountain of boxes of peppermint tea. Let’s get them, I urged, we can make tea. But that won’t fill us up, Beate explained. Our resourceful mother found a little white linen coat for an infant and with colored threat from here and there embroidered the coat’s collar and cuffs. She offered the coat as a gift to a farming couple who were about to baptize their baby daughter. They accepted the gift and begrudgingly handed Mutti a handful of potatoes. Our mother went begging and Beate was her most stellar support. They would walk to the country with a knapsack, knocking on farmers’ doors, offering whatever household item Tante Anneliese could spare. But most of the time the farmers didn’t answer the knock or shut the door into their face. Mutti and Beate returned empty-handed and exhausted.

Sometime during the summer one of Papa’s colleagues, Herr Richter and a deaconess, arrived at our doorstep with the good news that Papa had survived in Berlin. We were able to house the visitors but how could we stretch the nettle soup to feed two more? We shared but I remember the hunger, greed, and humiliation around the kitchen table.

It was August when Mutti decided that the family should be reunited in Berlin, a city bombed to smithereens. Mutti, Beate and I would go first, leave me there and then return to get Heidi and Claudia. There were no train schedules, hardly any trains, and destroyed tracks meant walking for miles to points of haphazard service. The trip, not more than six hours in normal times, took several days. For provisions, Beate and Mutti concocted a soupy potato salad with Beate’s engagement ring swimming in the goo. They were determined to hide it from the Russians who were swarming everywhere, collecting jewelry and wrist watches as they spotted them. It was hot as we set off and we waited with hundreds who were also stranded and destined to somewhere and nowhere. The few trains that would arrive were quickly overcrowded. Eventually Mutti and I were pressed like sardines in a compartment, while people crowded the roof, and on one stretch Beate hung on outside with one foot on the running board. She was scared and brave as the coal-fueled train, huffing and puffing, went through dark tunnels and over rickety bridges. Flying sparks from the locomotive at one point ignited the clothing of a young boy whose screams halted the train. The boy was rolling on the grass to extinguish the flames as our train moved on, leaving him and his mother behind. I registered the scene without emotion. We were in survival mode without feelings to spare.

One late afternoon, waiting for another train at a bombed-out station, Russian soldiers started to appear as the sun was casting its shadows. “We better get out of here,” said Mutti. But where to go? We moved toward the little town and knocked on the door of a house with a pretty front yard. Miraculously, a friendly woman agreed to shelter us for the night. I remember sleeping under a red featherbed without a slipcover. Beate and Mutti whispered next morning about the screams of women from the nearby station.

Walking, waiting, riding overcrowded trains got us early one morning to Berlin. Public transportation was barely functioning and while Beate stayed with the luggage, Mutti and I set out to the Bethany Hospital in Steglitz where Papa had survived street fighting and capitulation. Walking along I remember seeing signs hanging from trees, “I am a traitor of the fatherland.” Mutti said that’s what deserters had to wear around their necks when they were hung on trees. I could swear I saw corpses dangling but that must have been my imagination. It was, after all, three months since armistice and surely burying these desperate soldiers must have been the first order of the day back in May.

Papa was just getting out of bed when we barged into his hospital room. We had last seen him six months earlier, in January. Events had separated us and we had escaped bombing, rapes and destruction by the skin of our teeth. Instead of hugs celebrating the miracle of survival or tears of joy over our reunion, Mutti confronted Papa like an accusing exclamation mark. And Papa, still sleepy and stunned, wasn’t exactly delighted to see us.

He had survived at the hospital, the only man among frightened-to-death patients and a female staff. When the first Russian soldiers stormed into the crowded basement, they pointed their gun at Papa, ready to kill. “Svečenic,” Papa yelled at them, Serbo-Croation for priest—a word he had picked up during his youthful internship in the Batschka, Yugoslavia. It worked. These young Russians, many from the hinterland (the tale went that they didn’t know what a toilet was and used it to wash their faces)—these young cannon-fodder boys crossed themselves and let Papa be. But they fancied the nurses, ready for rape. “Resist,” Papa told the women, “fight,” he coached, knowing full well that if he interfered he’d be dead.

Beate who knew Papa’s story well, said that he was able to keep the deaconesses and nurses from harm, save a kitchen maid who exited the basement with flirtatious flair.

Later the hospital was filled with women who had been gang-raped. When the Americans finally entered the city and came to take over the zone around the Bethany Hospital, Papa took them on tours. “She was raped 40 times,” he’d explain, letting them peek into a hospital room. “This young girl endured dozens of rapes,” he’d say, pointedly reminding the Americans of the beastly behavior of their allies.

Papa, the sole male during the nightmare, became the hospital’s hero. But not to Mutti who felt that he had abandoned the family by leaving on a convenient business trip while the Russian front was thundering.

So, after their frosty greeting, Mutti demanded that Papa now come and retrieve Beate and the luggage. I settled into the second bed in his room and had a good sleep.

Papa and I stayed in that room while Mutti and Beate returned to Annaberg to get Heidi and Claudia and our precious featherbeds. Papa started to look after his newly assigned congregation on Tilsiter Strasse in East Berlin. The church was a heap of rubble and with help from a few congregants, Papa had started clearing the site in hopes of building a new church (which he eventually did).

Looking back I realize that we were shocked survivors. There was no time for feelings, good or bad. “Reiss dich zusammen, (Get a grip)” was one of Papa’s favorite mottos. He modeled his motto excellently and showed contempt when we failed, especially towards Mutti who was prone to indulge her feelings and easily fell apart.

While Papa and I lived together, he would pace up and down in the evenings trying to memorize Russian vocabulary. He thought that in the years to come he would need it. Luckily, he and we didn’t. Our lives had hit rock bottom and we were crawling out of devastation, fear, and starvation into a period of recovery.

When school started in September, Papa enrolled me in third grade, although I had missed half of second grade. He assured the principal that I’d catch on and master my multiplication tables within a few weeks. Every evening we’d sit on a bench in the lovely hospital garden and he’d quiz me: three times four, five times six, three times nine, etc. I’d be wrong half the time, eliciting his groan of exasperation. I had no idea what the multiplication tables were all about and tried hard but often failed to memorize the numbers. Teaching elementary school twelve years later I took great pains explaining the multiplication concept to my students, remembering with a shudder my times with Papa on the bench.

Once the rest of the family had joined us, we moved into a larger hospital room, Claudia and Heidi were enrolled in school and Mutti and Beate roamed the woods for mushrooms and anything eatable. We were still hungry but not starving. We had regular meals with the staff in the dining room and for breakfast a dab of Schmalz (lard) with bread because one courageous deaconess had retrieved a whole barrel of Schmalz at some distribution center and rolled it all the way to the hospital through left-and-right explosions during the waning hours of the war. While the sisters were friendly and tolerated our stay, we were dying to move into our own four walls.

In September a Lutheran minister offered Papa an elegant apartment on Stindestrasse on the other end of Steglitz. It had been occupied by a lawyer who was a member of the Nazi party. He and his family had been evicted. The Lutheran minister who also needed housing told Papa that he couldn’t possibly move into the apartment because he had baptized and confirmed the man’s children. But the Kreutzers who didn’t know these people could move in, reasoned the Lutheran and so we moved into the five-room apartment with winter garden, sliding glass doors, parquet floors, and a calling system wired to the maid’s room behind the kitchen. We got some rickety cots from bunkers, parishioners from Papa’s former church at Ruegener Strasse brought furniture, and at a huge depot Mutti chose antiques available for victims of the war, taken from the perpetrators of the war. With his last deutsche mark Papa bought a grand piano. In those days you could buy a piano but no bread.

With Heidi playing we usually assembled around the piano in the evening, sang hymns, folk songs, and Lieder. There was a bus stop right below the living room window and those waiting would look up and listen stoically to the harmonies from above. They looked haggard, emaciated, ragged and I imagined them thinking ‘how come these people are so happy?’ And I wanted to tell them, ‘we’re the same as you. We’re hungry and cold and we’ve lost everything, including my beloved doll, and like you we can’t think of anything but bread and potatoes, and we’re feeling weak from all this yearning. But we’re singing and making music, and yes, it makes us feel a little better and hopeful.’

Papa told us over watery soup at night that he had felt faint walking through the rubble of Berlin that day. He had sat down on the curb and had waited until the feeling of total exhaustion due to an empty stomach had passed. And Mutti had opened the door to a woman, a grandmother who was begging for bread for her starving grand-children. And Mutti went into the kitchen and came back with a crusty end piece of our bread and gave it to her. “Why did you do that?” I asked. “I’m hungry and I love the crusty ends because they take longer to chew, it’s like having more to eat.” And Mutti just shrugged and said she had felt sorry for the woman.

It was around that time that I remember Mutti looking out the window without focus, quietly crying. She had learned that her parents had died in one of Tito’s concentration camps in Yugoslavia. The news was received without drama. Papa later wrote an article for the Evangelist, the Methodist monthly, telling the story of the tragic fate of these stranded Germans under new communist rule. Reading his story you wouldn’t know that he was writing about his in-laws. Being stoic and self-effacing was a top virtue in our household.

Driven by our daily hunger pangs, Mutti and Beate went sometimes to the country begging door-to-door. Mutti would take a dress I had worn out, embellish it with some embroidery and offer it to the farmers’ wives in exchange for potatoes, bread or carrots—farmers could afford to be choosy in those days and often slammed the door. Public transportation was intermittent and sometimes lacking, making them walk for miles.

They were returning from one such exhausting outing with an empty rucksack when I whispered to them excitedly that three American soldiers were sitting in our living room. An hour earlier I had opened the door to them and deciphered that they wanted to meet with Papa. Mutti’s energy immediately rallied and she joined the group, quickly dominating with her still fluent English from her years at the American college.

The Americans had been in the airborne division, the first contingent to arrive in the bombed-out capital, taking over the western part where we lived. Eager for contact with English-speaking Germans, they had learned of Papa who had served a German congregation in London for a year after seminary. That first encounter with the Americans led to an invitation from American chaplains to come to an evening meeting in Mariendorf. Bicycling through the dark streets and over a make-shift bridge spanning the canal, Papa was hit by a drunken G.I. and thrown as “German pig” into a ditch. His bike was bent and he had to push it for the last kilometer. He arrived late and muddied. The Americans, all set to extract a mea culpa from this German, apologized instead and ushered him into the washroom to clean off. After a long session, a jeep brought Papa and bent bike to our doorstep. Still euphoric about the evening, Papa rallied us from sleep to tell his story and share a big bag of spongy round cakes with a hole in the middle, our first taste of donuts.

It was early fall and Heidi, Claudia and I had settled into partially bombed schools in the neighborhood. But what about Beate? In Schneidemuehl she had started at a Frauenfachschule, a home-economics school and thus enrolled in one in Berlin. She gave up after scrubbing floors and clearing rubble from the partially destroyed building and then being asked to bring to school all the ingredients for a potato salad so she could be taught how to make one. Ridiculous, Beate and Mutti agreed. We were still hungry, had little food, bartered with farmers, and Beate was best at spotting hitherto unknown mushroom varieties in front-yards and city parks. Were they eatable? We cautiously tried them and didn’t die.

Through his connections with the chaplains Papa learned of opportunities for his two attractive teenagers to work at the American Red Cross coffee shop. Beate embraced the idea with enthusiasm. Sure, she could learn English over-night, and sure, she could pour coffee and offer donuts to American servicemen while eating dozens herself, yumm! For Heidi who diligently memorized her Latin and French vocabulary hoping to matriculate and study music, the transition to coffee shop waitress was traumatic. Though Heidi was soon feted and courted for her expert piano playing, Beate brusquely brushed off suitors with her engagement ring. But where was her fiancé? Beate had no idea. The last she had known, Werner was a captain on horseback on the Eastern front, commanding 250 men. If still alive, he would be a prisoner of war in Russia by now.

Meanwhile we lived on donuts. The Americans didn’t allow German employees to carry out any food but Beate smuggled the first donuts in her bras. If the cafeteria and coffee shop had leftovers the Americans burned the food, enraging starving Germans who looked on. I remember waiting with Claudia one night outside the barbed wire surrounding the American Red Cross as Beate hastily handed us a package of yesterday’s donuts. By the time we were sick and tired of hot and cold donuts for breakfast, lunch and in casseroles for supper, Germany’s food supply system had kicked into gear and we received meager rations of potatoes, flour, and powdered milk.

On Papa’s birthday in October we had enough Stipp (raw potatoes grated into boiling water with a bit of salt) to invite three American soldiers who had become friends. We had beautiful china Mutti had bartered from a bed-ridden old lady on the third floor, and we had the silver cutlery Claudia had rescued in her suitcase.

I felt so excited about sharing our evening meal of Stipp. I just knew that the Americans would love it. And so I watched Randsdel who sat opposite lift his spoon, tasting, shaking his head, putting down the spoon saying that he couldn’t eat this. The two others followed suit. I felt ashamed and Papa let out an embarrassed little laugh. How could they, what a waste, I thought, but perhaps we could boil their portions and eat more afterwards.

Three months later, by Christmas 1945 we were back to familiar rituals. Christmas Eve was always a solemn, holy affair with everyone standing around the tree in our Sunday best, Papa reading from Luke, followed by prayer and all the verses of O, du froehliche and Stille Nacht. We knew how to do this, even after a year of nightmares, losing our home and all our goods, transplanted into Berlin’s rubble, suffering from hunger and frost bite.

We had a tree. It was sparsely decorated and there were even a few presents. Best of all, there was Stipp for supper, enough to have your fill. Beate was so enthusiastic about Stipp that she swore to serve lots of it, all you can eat, at her wedding. She wore her gray-black engagement dress and fingered her engagement ring. She still had not heard from Werner, did not know whether he was alive. During Stille Nacht she felt overcome with grief. She shook violently, tears streaming down her face and we kept singing about a holy night and parents, shepherds and angels adoring a new-born baby. Beate’s emotional outburst was contrary to protocol and a bit embarrassing. With Papa leading the way, we kept singing. There were no words of compassion for this 19-year-old girl whose love and dreams had collapsed. Being Beate and a Kreutzer, she did pull herself together by the time we were through. I can’t remember much about the rest of the evening but assume that Beate, resilient by nature, ate Stipp with her usual gusto.

The other night I watched a TV documentary on the Buddha and learned a lot. He sat under his Bodi tree, teaching the new insights he had figured out when he receives a message that the people in his father’s kingdom, including his wife and son, had been massacred by some invading hordes. The Buddha listens and says nothing, just continues to sit there. In his teaching he says that in this life suffering and death are inevitable and most of our suffering comes from denying that reality.

Well, we Kreutzers were little buddhas without knowing it. Keep going, acknowledge the inevitable, lighten up. At eight, I was very much for lightening up. There is the school of thought that you should tear out your hair and shred your clothes and, according to the Buddha’s bio, he did that a lot until he realized that that wasn’t the path. Living in the present moment was.

And Christmas 1945 was our celebration of survival, although Beate ached with the uncertainty of not knowing whether she would ever see the love of her life again, and our family living with the certainty that our grandparents, who had spoiled us with the abundance gathered from their fertile lands, had starved to death and were buried in a mass grave.

After Christmas Beate received a postcard from Werner sent through the Red Cross. In tiny handwriting to make the most of the card’s space, he told her that he may never return and she should not feel committed to their relationship. “Ich gebe dich frei (I release you from your promise),” he said. His gallant gesture from Belarus triggered torrents of tears because Beate felt committed for life, and in her response she let him know that. In a subsequent postcard Werner hinted that, should he ever come home, he was going to dedicate his life to Christian ministry.

That was quite a career switch, since Werner had planned, following in his father’s footsteps, to join the bureaucracy of the Reichsbahn, the national railway, and given his talent for leadership, Beate had fancied herself becoming the wife of Herr Reichsbahnrat, the head honcho. Instead, if she ever got to marry Werner, she’d be the wife of a Methodist minister.

Ever resilient and responding to Werner’s hint, Beate decided to prepare for the ministry herself, either fulfilling his intentions or, God willing, becoming his partner. Her decision coincided with the end of a short-lived teaching career.

After their stint at the American Red Cross, Beate and Heidi had been hired as pre-school teachers at the newly-founded American school in Dahlem. As U.S. military personnel settled into the divided city, families arrived by the plane-load, children needed to go to school, toddlers needed pre-school. Though they couldn’t produce any certificates or document training, Beate and Heidi had been hired as able, warm bodies who could teach American cuties “A,B,C,D,E,F,G…”, play “Ring around the Rosie,” and sing songs in English and German. Miss Beatrice and Miss Heidi were a hit with the kids and their parents and many new friendships evolved, getting Heidi also to teach private piano lessons. But when Heidi married Hans, a dentist in East Berlin, Beate’s contract was canceled. By then, Berlin had become the Cold War center of spies, and after the scandalous defection of a U.S. officer to Russia, all relationships between East and West were carefully monitored.

Beate transitioned into the Missionsschule in Marienfelde without much ado. The Protestant school was preparing young women to become teachers of religion or assistants to ministers at home or abroad and was the most common path for women into ministry in those days.

The Missionsschule was a boarding school with strict rules of study hall and lights-out. When Beate came home on weekends, usually walking for an hour along a canal, she was always bursting with news and learning from the classroom and I remember how she and Mutti discussed Paul’s theology and John’s eschatology like the day’s hottest news. I listened with some resentment, understanding little, feeling how exclusive their relationship was. Mutti and Beate grooved on each other.

At the school Beate quickly became every student’s best friend, brought many of them home and had Mutti talk about her own youthful stint of mission work in Macedonia. Mutti would describe the endless sky over the steppes, radiant sunsets, and occasional mirages. She had a mesmerizing way of spinning her stories as Beate leaned back, proud of her accomplished mom. She also invited her teachers, two elderly spinsters, to join the family around the dinner table and piano. Fraeulein Schubert joined heartily when we sang Freude schoener Goetterfunken, the rousing finale of Beethoven’s Ninth, but then got reprimanded by Fraeulein Harder, the more fundamentalist of the two. “How can you sing ‘ueberm Sternenzelt muss ein lieber Vater wohnen,’” she demanded, implying that a God-loving Christian knows and doesn’t just speculate about a loving father beyond the firmament. Clearly, the Missionsschule taught certainties, Schiller’s or anyone else’s doubts were out.

Papa was pleased with Beate’s educational development. She now earned the As she had always dreamed of. “I only study what really interests me,” she’d explain with a shrug when asked to explain her previous academic zigzags. When the time came for Beate to do her internship, Papa arranged for her to serve a church in Birmingham, England. At that time Claudia was already in nursing school in Huddersfield. Papa liked for his girls to explore the world and get an education. He also liked to talk theology with his oldest daughter. Years later, after his retirement and move to Groetzingen, he once approached Beate with a thick tome in his hand, “What do you make of Luther’s tower encounter, Beate?” She was standing high on a ladder helping Mutti hang curtains in the new apartment. “I’m right now in a tower encounter and wish you had one too,” she countered. He quickly disappeared into his study. Papa lived mostly in his head and was hopelessly inept at household chores. At times we liked to rub it in.