Tri-City Herald, Sunday, December 9, 2001

U. S. Postal Service Honors Mexican Artist

©2001 Valerie Kreutzer

Frida Kahlo's feminist mystique still inspires.

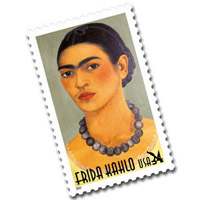

You may not know Frida Kahlo yet, but once you have seen the Mexican painter’s bewitching face with its bushy arching eyebrows, you’ll recognize her image everywhere. Even on a U.S. postage stamp.

You may not know Frida Kahlo yet, but once you have seen the Mexican painter’s bewitching face with its bushy arching eyebrows, you’ll recognize her image everywhere. Even on a U.S. postage stamp.

Frida Kahlo (1907-54) is part of the U.S. Postal Service’s “New Century of Stamps”—right between Lucille Ball, Peanuts, Carnivorous Plants, and Leonard Bernstein.

Her work has significantly influenced Chicana artists in the United States, and since the mid-70s she has been a role model for women in the Mexican-American and feminist communities,” the Postal Service explains.

Kahlo was born in Coyoacan, now part of Mexico City. Her father was an Austro-Hungarian Jew, a photographer and immigrant, her mother was Mexican. While attending a preparatory school at the age of 18, the bus she was riding was hit by a trolley and a metal rod punctured her abdomen. Her spinal column was broken in three places; her pelvis was fractured; her collarbone, two ribs, her right leg and foot were broken; her left shoulder was dislocated. The accident added to the trauma of polio she had suffered as a child.

It was during the lengthy recuperation that Kahlo began painting. Lying in her four-poster bed, she studied her reflection in the mirror attached to the canopy. “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best,” Kahlo once said.

Needing assurance, Kahlo sought the opinion of Diego Rivera, a well-established artist and muralist, twenty years her senior and a married man-of-the world.

“As soon as they gave me permission to walk and to go out in the street,” Kahlo once told an interviewer, “I went carrying my paintings to see Diego Rivera, who at the time was painting the frescoes in the corridors of the Ministry of Education.… I was bold enough to call him so that he would come down from the scaffolding…. ‘Look, I have not come to flirt or anything even if you are a woman-chaser. I have come to show you my painting. If you are interested in it, tell me so.” Rivera reviewed her work and declared: “You have talent.”

During their ensuing courtship, Rivera painted Kahlo often as ideological symbol into the large murals that depict Mexico’s history and political struggles. Like many artists and intellectuals in post-revolutionary Mexico, Rivera was a card-carrying Communist. Kahlo also joined the party, and to please her lover further, she began to dress in colorful and embroidered regional costumes, wore exotic jewelry, and piled her black hair into a braided crown. The diminutive artist and the colossal muralist made an odd couple. “It was like the marriage between an elephant and a dove,” Kahlo’s parents said at the wedding in 1929.

During the first years of their marriage, the couple lived in different houses around Mexico City. They frequently traveled to the United States, where Rivera quarreled with his industrialist patrons over the Marxist visions in commissioned murals. Kahlo continued to paint in hotel rooms. The fierce candor of her self-portraits also included her agony over childlessness after she had two miscarriages.

In “Henry Ford Hospital (Detroit),” Kahlo paints herself naked on a hospital bed, weeping and hemorrhaging, with a fetus hovering above—not a painting to hang over the couch in your living room. “Frida,” Rivera once said, “is the only example in the history of art of an artist who tore open her chest and heart to reveal the biological truth of her feelings…. (She is) a superior painter and the greatest proof of the renaissance of the art of Mexico.”

The couple eventually settled in the Blue House in Coyoacan, Kahlo’s birthplace, and now the Museo Frida Kahlo. The house’s deep indigo and terracotta walls contrast with dark green window frames and doors. Walls surround a garden of luxurious foliage, home of the monkeys and exotic birds that entered many self-portraits. It is a fascinating place to visit because it tells us about the artist’s life and times.

There is the famous four-poster bed with its mirror next to her wheelchair. The palette and brushes on the worktable look as if they’ve just been put down. Next door, in Rivera’s bedroom, are his Stetson, his huge overalls, and big miner’s boots. The walls and shelves throughout the house are crowded with art and indigenous artifacts.

My favorite is the blue and yellow kitchen with rustic clay pots and tiled counter-tops. Here Kahlo concocted black mole, enchiladas, and tamales for family feasts and national holidays. But life in the Blue House was not always a fiesta.

Kahlo’s frail health deteriorated. Numerous operations eventually led to the amputation of her right leg. She also experienced raging jealousy and loneliness in the face of her husband’s frequent infidelities. In 1939, the couple divorced, only to remarry a year later. After Kahlo died in 1954, Rivera remarried but died three years later. He missed her guiding spirit and inspiration. She was his muse.

The largest collection of Kahlo’s work—over 20 paintings—is displayed at the Museo Dolores Olmedo Patino, a grand estate that belonged to Rivera’s long-time mistress and last wife. The Mexican government has declared Kahlo’s paintings “artistic patrimony,” meaning that they cannot be sold to foreigners. The few paintings already abroad, are highly valued. In 1991, one piece was auctioned for five million dollars, a record for a Latin American work of art. When Madonna recently lent her Kahlo painting to a London museum it made international news.

The National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C., is the proud owner of a Kahlo self-portrait. It is displayed at the top of the grand staircase and seems to have a room of its own. The painting shows the artist standing between parted curtains in traditional Mexican ruffled dress, holding a bouquet and a note: “For Leon Trotsky with all my love.” The Russian revolutionary who had been ousted by Stalin, was granted political asylum in Mexico, due to Rivera’s efforts. The Trotskys lived in the Blue House for a while and later found a home around the corner. Kahlo had a brief affair with Trotsky, and the portrait was a gift to her lover on his birthday.

Admiring the portrait at the Museum of Women made me want to hit the Frida trail. When the Dicksons, my foreign service friends, were posted to Mexico, I asked whether they would like to visit the Kahlo landmarks with me. “Sure,” John and Mary said, “but who is Frida Kahlo?” It didn’t take them long to spot her ubiquitous image.

There is Frida distributing arms to revolutionaries in a Rivera mural at the Ministry of Education. And listening to ranchero music at the university, we nudged each other when we discovered a pig-tailed Frida in the mural at the front of the auditorium.

We made a sport of spotting Frida images rendered on paper and in clay, on souvenir coasters and mugs. “Frida-mania” Julieta Gimenez Cacho of Mexico’s National Council for Culture and the Arts has called this preoccupation with the Kahlo mystique. “She had a strong personality and was a very important figure,” Cacho allowed during an interview, “but there is more to Mexican art than Kahlo and Rivera.”

No doubt. But for now, the United States has caught the fever. When I sent my friends a sheet of the commemorative stamp, John promptly framed and hung it on the wall of his embassy office. His Mexican visitors will be interested to know that their icon has entered the American mainstream.