Tri-City Herald, Sunday, June 10, 2001

Gorgeous Guanajuato

©2001 Valerie Kreutzer

Mexico's Colonial Jewel is a World Heritage Site

Nestled into a narrow canyon between steep mountains of Mexico’s central highlands lies beautiful colonial Guanajuato, listed by UNESCO as a world heritage site.

Nestled into a narrow canyon between steep mountains of Mexico’s central highlands lies beautiful colonial Guanajuato, listed by UNESCO as a world heritage site.

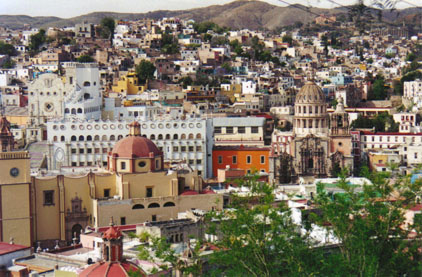

Looking from the hills over Guanajuato’s compact maze of winding lanes and cobblestone steps opening to charming plazas and grand churches, you can easily forget the 21st century and feel but a heartbeat away from the city’s colonial past and the most glorious moments in Mexico’s struggle for independence.

Historically, Guanajuato was a thriving center of agriculture before silver was discovered in the surrounding mountains in 1554. By the turn of the 18th century, it was the richest city in Mexico, producing more than one third of the world’s silver. The Spanish silver barons lived opulent lives at the expense of the indigenous people who worked the mines, first as slave labor and then as wage slaves.

In 1810, the town was ripe for revolution when Father Miguel Hidalgo’s ragtag army of farmers and mine workers arrived. They chased the wealthy land and mine owners into the Alhondiga de Granaditas, the huge square building that served as a granary in the center of town.

At the Alhondiga, the royalists defended themselves by dropping oil and molten lead on the insurgents who attempted to beat down the door. But a scrawny-necked man, nicknamed Pipila, had fellow-miners lash a heavy stone slab to his back, and thus protected, he started a fire on the building’s main door. After the blaze destroyed the door, the insurgents rushed the granary and killed the Spaniards right and left.

Their victory didn’t last long, and when the Spaniards regained control, their revenge was ferocious. They beheaded the revolutionary leaders and hung their heads from the four corners of the Alhondiga. They also invented an infamous lottery, randomly choosing citizens to be tortured and hanged.

After independence from Spain in 1821, the redistribution of wealth created a new upper class that showed off its status by building elegant mansions. In the early 1900s, a social revolution and religious conflicts brought again violence to the city.

Today, Guanajuato is a prosperous university town and the capital of a state that shows the lowest unemployment in Mexico and an export rate three times the national average. Its progressive governor, Vincente Fox, became Mexico’s president last year. In February, the newly elected Mexican and U.S. presidents met at Fox’ hacienda near Guanajuato. It was President Bush’s first state visit. He didn’t get to see the colonial city, but most travelers wouldn’t want to miss it.

A tour of Guanajuato usually starts under Pipila’s huge stone statue high above the town. During a recent visit to the lookout, I was surrounded by hundreds of uniformed school children on an outing, attentively listening to their teachers’ explanations of the historic landmarks laid out at our feet.

They pointed to the Alhondiga, now a museum of history, and recounted the daring feats of Pipila, hovering above us. And the large white building over there is the university, the guides explained. It was begun by Jesuits in 1732 to educate the wealthy sons of the mining families. Today it is a state university and considered one of Mexico’s finest for music, theatre, mine engineering, and law.

The university has 21,000 students and their presence dominates in this town of 70,000. Add to this residential mix the many school kids from kindergarten to high school who come on day trips to have a look at their Mexican heritage, and you soon wonder whether enough adults are in charge of this place. Especially, if you come from nearby colonial San Miguel de Allende, a gringo town where retirees rule.

The youthful culture of Guanajuato is most evident on weekends at the central Jardin de la Union, a tree-shaded tiled plaza with an old-fashioned bandstand that is surrounded by side-walk cafes, bars and restaurants. While the tourists crowd the restaurants for excellent food and fine people watching, the young people pack the steps of the elegant Teatro Juarez to be entertained by mimes and clowns who practice their craft often at the expense of good-natured tourists.

“You’ll have to push yourself through a wall of students,” warned the woman who had told me about the excellent Friday symphony concerts, just off the Jardin. For an equivalent of four dollars I got to hear two Brahms piano concertos. I also learned that half the orchestra hails from Eastern Europe where state support for the arts has decreased since the fall of the Communist dictatorships. Over the past decade, many Eastern European musicians have found jobs and new homes in Mexico.

My neighbor David came from Alaska. He was taking a four-week Spanish course at the university. He was enthusiastic about the intensive that included Mexican history, literature and a language lab for practice. The tuition was $500 and the university had also helped him find a room with a local family for $100/month.

When I expressed interest in the course, David warned that the language department is on the top floor of the building, 197 steps from the street. “I’ve counted them,” he said with a laugh. “By now I’m used to the daily climb.”

Ah yes, the steps of Guanajuato! I didn’t count them, but I must have climbed at least 1,000 steps on my first day. This place is definitely not wheelchair accessible. Even the room in my first-rate hotel was 50 steps up, and the beautifully tiled bathroom had another five steps leading to the shower!

But walking and climbing you must, if you want to catch the awesome vistas over rooftops and mountains, or catch local life in the twisting and narrow alleys, such as the Callejon del Beso, the Alley of the Kiss. It is so narrow that, according to folklore, lovers could exchange furtive kisses from balconies at opposite sides of the alley.

A less obvious landmark is the Museo Casa Diego Rivera, the house where the painter and muralist was born in 1886. It displays his family’s furniture and life style and some of his paintings, including a lovely nude of Frida Kahlo, Rivera’s student and wife. The Marxist artist was once a persona non grata in conservative Guanajuato, but today you have to pay admission to look at his bourgeois roots.

Walking along the alleys, I found traffic from automobiles relatively light thanks to a subterranean highway system that runs the length of the town.

The tunnels follow the bed of a river whose wild floods used to tear up the city. But the river was dammed and now you can drive from north to south through arched stone tunnels underneath the buildings.

If walking or riding through the barely lit tunnels spooks you, you should definitely skip Guanajuato’s most popular tourist attraction, the Mueso de las Momias.

The museum houses the mummified bodies of local citizens who have died over the past 150 years and were exhumed when families no longer paid for cemetery graves and space became scarce. Gravediggers discovered that the minerals-rich soil had preserved the corpses very well. Propped up in glass cases that line a narrow tunnel, some mummies still wear their boots and ragged suits, and children are dressed up like dolls.

Our guide heightened the macabre scene by pointing to the corpse of a young woman. Her arms were stretched out as if in desperation, although her family had buried her with arms folded. “She was probably buried alive,” said the guide.

To cheer myself, I spent the next two days in the countryside.

The Ex-Hacienda de San Gabriel de Barrera is set amidst magnificent gardens and furnished with European antiques from the 17th-19th centuries. It illustrates the life of the wealthy mine owners from private chapel to very private chamber pots. Sipping freshly squeezed lemon juice in the little outdoor restaurant, I imagined living the charmed life of a hacienda matron.

My last outing took me to Valenciana where silver mines produced 30-40% of the world’s silver for two centuries. The church of San Cayeto, built in the 18th century by a mine owner, shows off the wealth that was once extracted from these bare mountains. The church’s interior dazzles with ornately carved altars trimmed in gold leaf.

A short walk from the church takes you to the only mine still operating. The days of hyperactivity are clearly over; the place looked almost deserted. From a depth of 1,500 ft, gray rocks rumbled over a conveyor belt onto a truck. In the course of an elaborate process, the rocks will yield a little silver, gold, nickel and lead. Barely enough to support the men who own the mine cooperatively.

Outside the gates, women displayed silver jewelry on large boards at attractive prices. In a gesture of farewell, I bought a pair of earrings. Before wrapping my souvenir, the vendor polished the jewelry to perfection. The silver sparkled in the Mexican sun and reflected the glamour of a rich heritage.