Tri-City Herald, Sunday, November 18, 2007

Toledo, Spain—a Place to Reminisce

©2007 Valerie Kreutzer

“You’ve got to see Toledo,” said Elke Foerstner, picking me up at the airport in Madrid. “It’s known as la ciudad de tres culturas—the city of three cultures.”

“You’ve got to see Toledo,” said Elke Foerstner, picking me up at the airport in Madrid. “It’s known as la ciudad de tres culturas—the city of three cultures.”

Elke, a high school classmate, knew her way around. After college she had settled in Spain, teaching school in Madrid. For the next few days she would be my tireless guide.

Toledo sits smack in the middle of Spain, is the country’s former capital, and a declared National Monument. To get there we chose the speed train for the 25-minute ride through rugged isolation. Exiting the train station, a 1919 marvel of Moorish (Muslim)-inspired architecture, Toledo rose before us on a gigantic mount.

Surrounded on three sides by deep gorges of the River Tajo, Toledo’s grey-beige structures are piled onto a rock that is dominated by a fortress and one of Europe’s largest cathedrals. Skipping the 20-minute hike to the main square, we opted for the local bus to take us to the main square, Plaza Zocodover. As we crawled up the hill, the city loomed large and seemed strangely familiar.

“El Greco lived and worked here,” Elke reminded me, as I recalled Toledo images the Greek expatriate had painted as backdrop for his saints and sinners. Arriving at the Plaza, tourists dispersed to track history, indulge in art, buy souvenirs, or catch vistas of the stunning landscape.

“Let’s start with the cathedral,” Elke suggested, leading the way through narrow alleys towards the shop that sold entrance tickets for a structure that took 250 years to build and epitomizes Spanish-Catholic domination over Jewish and Muslim cultures. Walking among the cathedral’s 88 pillars and 20 chapels, you can’t help but feel awed by the genius and craftsmanship that created the 500-year-old stained-glass windows, or the colorful story-telling frescoes. Carvings in the choir stalls record the 15th century Christian conquests of Moorish cities whose occupants were driven back to Africa.

On the walls of the sacristy hang 20 El Grecos, the most famous among them The Denuding of Christ, depicting the mob that stripped Jesus of his robe before his crucifixion. At the nearby Santo Tome chapel hangs another El Greco masterpiece, The Burial of the Count of Orgaz. In this painting, the count’s body is laid to rest by saints, and his soul is being received into heaven. El Greco painted himself and his son into the group of onlookers. The 16th century master brought to his paintings the mystery of Greek-Orthodox icons, and the bold colors and drama of Italian Renaissance. He made Toledo his home and the town displays his work everywhere.

After all this dazzling art, my body craved some sustenance. It was noon, where could we have lunch? “Not before 2 p.m.,” Elke informed, reminding me of the Spanish custom of late meals. “Let’s buy some marzipan,” she suggested, entering the doorway of a modest façade. A glass cage displayed almond-fruity roses, angels, loaves and fishes. A bell next to the display summoned a cloistered nun who opened a little window behind an iron grid. We ordered and put euros on the turnstile. “Don’t touch her,” whispered Elke, reminding me of cloister etiquette. After the transaction, the nun quickly disappeared behind her bars.

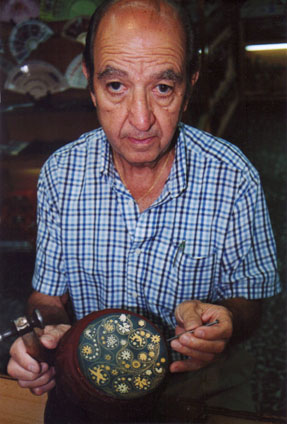

Next, we ventured into souvenir and antique shops, offering medieval armor, swords, and lethal-looking knives, decorated with the damascene patterns typical of Arab artistic traditions and Toledo craftsmanship. At one of the stores we watched an old master assemble tiny bits of gold, silver and copper wire into the black background of a metal plate. “I’ve been at it for over sixty years,” he explained. “Young people don’t apprentice anymore. It’s a dying art.”

It seemed that all of Toledo was about a glorious past. During the city’s heyday in the Middle Ages, Toledo was famous for intellectual tolerance. For 300 years, Jews, Moors, and Christians lived in harmony, calling God by different names.

“That golden time ended when Ferdinand and Isabel, the ‘Catholic Monarchs,’ expelled Jews and Moors in the 16th century,” Elke explained over lunch at the cave-like Monilo restaurant. Our four-course menu with pork roast included a generous carafe of red table wine and came to less than $50.00 for two.

Fortified, we headed towards two more sites that showed how east and west once fused and flourished here.

In the Jewish Quarter, the 14th century Synagogue del Transito exemplifies the close Jewish and Arab sensibilities in carvings and Moorish-style columns. The adjacent museum recalls the story of the Jews—called Sephardim—who lived in Spain after escaping Roman persecution in Palestine.

Not far from the synagogue is an archeological dig revealing remnants of a mosque that was built at the end of the first millennium. As with other Jewish and Moorish sites, a church was superimposed upon the structure. Today, the ruin is called Christ of the Light Mosque.

In late afternoon we returned to the Plaza Zocodover, where old men lined the benches. “Old men sitting at the plaza, watching—that’s so typically Spain,” observed Elke. The oldest among them lived through the 1936-39 Civil War when Toledo was the scene of a bloodbath, followed by General Franco’s victory march into the city.

From the train station we took a last look at the towering citadel. Grey clouds hovered above the spires—as if painted by El Greco.